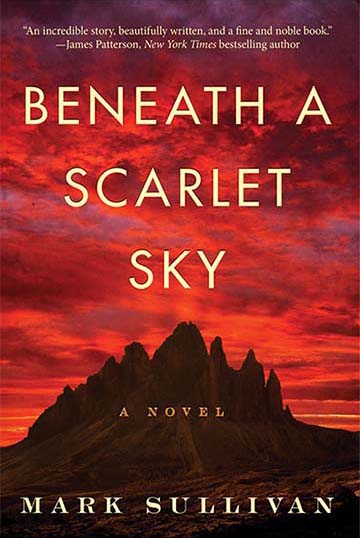

Based on the true story of a forgotten hero, Beneath a Scarlet Sky is the triumphant, epic tale of one young man’s incredible courage and resilience during one of history’s darkest hours.

Pino Lella wants nothing to do with the war or the Nazis. He’s a normal Italian teenager—obsessed with music, food, and girls—but his days of innocence are numbered. When his family home in Milan is destroyed by Allied bombs, Pino joins an underground railroad helping Jews escape over the Alps, and falls for Anna, a beautiful widow six years his senior.

In an attempt to protect him, Pino’s parents force him to enlist as a German soldier—a move they think will keep him out of combat. But after Pino is injured, he is recruited at the tender age of eighteen to become the personal driver for Adolf Hitler’s left hand in Italy, General Hans Leyers, one of the Third Reich’s most mysterious and powerful commanders.

Now, with the opportunity to spy for the Allies inside the German High Command, Pino endures the horrors of the war and the Nazi occupation by fighting in secret, his courage bolstered by his love for Anna and for the life he dreams they will one day share.

Fans of All the Light We Cannot See, The Nightingale, and Unbroken will enjoy this riveting saga of history, suspense, and love.

- #1 AMAZON CHARTS MOST SOLD & MOST READ BOOK

- A WALL STREET JOURNAL Bestseller

- USA TODAY BESTSELLER

“An incredible story, beautifully written, and a fine and noble book.” —James Patterson, #1 New York Times Bestselling Author

“Beneath a Scarlet Sky has everything—heroism, courage, terror, true love, revenge, compassion in the face of the worst human evils. Mark Sullivan was born to write this novel based on the real story of Pino Lella, one of many unsung heroes of the Second World War. It’s gripping, shocking, heartbreaking and ultimately inspiring. Sullivan shows us war as it really is, with all its complexities, conflicting loyalties, and unresolved questions, but most of all, he brings us the extraordinary figure of Pino Lella, whose determination to live con smania—with passion—saved him.” —Joseph Finder, New York Times bestselling author of Suspicion and The Switch

“Sprawling, stirring, like the richest of stories, and played out on a canvas of heroism and tragedy, Beneath a Scarlet Sky is like one of those iconic WWII black and white photos: a face of hope and tears, the story of a small life that ended up mattering in a big way.” —Andrew Gross, New York Times bestselling author of The One Man

“This is full-force Mark Sullivan—muscular, soulful prose evincing an artist’s touch and a journalist’s eye. Beneath a Scarlet Sky conjures an era with a magician’s ease, weaving a rich tapestry of a wartime epic. World War II Italy has never been more alive to me.” —Gregg Hurwitz, New York Times bestselling author of The Nowhere Man

“Action, adventure, love, war, and an epic hero —all set against the backdrop of one of history’s darkest moments—Mark Sullivan’s Beneath a Scarlet Sky has everything one can ask for in an exceptional World War II novel.” —Tess Gerritsen, New York Times bestselling author of Playing With Fire

They crossed the Po River, and long before dusk, while the countryside still lay blanketed in summer torpor, the train squealed and sighed to a stop amid gently rolling farmland. Pino carried a blanket over his shoulder and climbed after Carletto to a low grassy hill above an orchard that faced southwest toward the city.

“Pino,” Mr. Beltramini said, “watch out, or there will be spider webs across your ears by morning.”

Mrs. Beltramini, a pretty, frail woman who always seemed to be suffering some malady or another, scolded weakly, “Why did you say that? You know I hate spiders.”

The fruit shop owner fought against a grin. “What are you talking about? I was just warning the boy about the dangers of sleeping with his head in the deep grass.”

His wife looked like she wanted to argue, but then she just waved him away, as if he were some bothersome fly.

Uncle Albert fished in a canvas bag for bread, wine, cheese, and dried salami. The Beltraminis broke out five ripe cantaloupes. Pino’s father sat in the grass next to his violin case, his arms wrapped around his knees and an enchanted look on his face.

“Isn’t it magnificent?” Michele said.

“What’s magnificent?” Uncle Albert said, looking around, puzzled.

“This place. How clean the air is. And the smells. No burning. No bomb stench. It seems so . . . I don’t know. Innocent?”

“Exactly,” Mrs. Beltramini said.

“Exactly what?” Mr. Beltramini said. “You walk a little too far here and it’s not so innocent. Cow shit and spiders and snakes and—”

Whop! Mrs. Beltramini backhand-slapped her husband’s arm. “You show no mercy, do you? Ever?”

“Hey, that hurt,” Mr. Beltramini protested through a smile.

“Good,” she said. “Now stop it, you. I didn’t get a wink of sleep with all that talk of spiders and snakes last night.”

Appearing unaccountably angry, Carletto got up and walked downhill toward the orchard. Pino noticed some girls down by the rock wall that surrounded the fruit grove. Not one of them was as beautiful as Anna. But maybe it was time to move on. He jogged downhill to catch up with Carletto, told him his plan, and they tried to artfully intercept the girls. Another group of boys beat them to it.

Pino looked at the sky and said, “I’m only asking for a little love.”

“I think you’d settle for a kiss,” Carletto said.

“I’d be happy with a smile.” Pino sighed.

The boys climbed over the wall and walked down rows of trees heavy with fruit. The peaches were not quite ripe, but the figs were. Some had already dropped, and they picked them up from the dirt, brushed them off, peeled the skin, and ate them.

Despite the rare treat of fresh fruit right off the tree in a time of rationing, Carletto seemed troubled. Pino said, “You okay?”

His best friend shook his head.

“What is it?” Pino asked.

“Just a feeling.”

“What?”

Carletto shrugged. “Like life isn’t going to turn out the way we think, that it’s going to go badly for us.”

“Why would you think that?”

“You never paid much attention in history class, did you? When big armies go to war, everything gets destroyed by the conqueror.”

“Not always. Saladin never sacked Jerusalem. See? I did pay attention in history class.”

“I don’t care,” Carletto said, angrier still. “It’s just this feeling that I get, and it won’t stop. It’s everywhere and . . .”

His friend choked up, and tears ran down his face while he fought for control.

“What’s going on with you?” Pino said.

Carletto cocked his head, as if peering at a painting he didn’t quite understand. His lips trembled as he said, “My mama’s really sick. It’s not good.”

“What’s that mean?”

“What do you think it means?” Carletto cried. “She’s gonna die.”

“Jesus,” Pino said. “Are you sure?”

“I heard my parents talking how she’d like her funeral to be.”

Pino thought of Mrs. Beltramini, and then Porzia. He thought about what it would be like to know his mother was going to die. A vast pit opened in his stomach.

“I’m sorry,” Pino said. “I really am. Your mama’s a great lady. She puts up with your papa, so she’s like a saint, and they say saints get their reward in heaven.”

Carletto laughed despite his sadness and wiped at his tears. “She is the only one who can put him in his place. But he should stop, you know? She’s sick, and he’s teasing her like that about snakes and spiders. It’s cruel. Like he doesn’t love her.”

“He loves your mama.”

“He doesn’t show it. It’s like he’s afraid to.”

They started to walk back. At the rock wall, they heard the strains of a violin.

. . .

Pino looked up the hill and saw his father tuning his violin and Mr. Beltramini standing there, sheet music in his hand. The golden light of sunset radiated off both men and the crowd around them.

“Oh no,” Carletto moaned. “Mother of God, no.”

Pino felt equal dismay. At times, Michele Lella could play brilliantly, but more often than not, Pino’s father would stutter his rhythm or squall through a section that demanded a smooth touch. And poor Mr. Beltramini had a voice that usually broke or went flat. It was excruciating to listen to either man because you could never relax. You knew some odd note was coming, and it could be so sour at times, it was, well, embarrassing.

Up on the hill, Pino’s father adjusted the position of his violin, a beautiful central Italian petite from the eighteenth century that Porzia had given him for Christmas ten years before. The instrument was Michele’s most treasured possession, and he held it lovingly as he brought it under his chin and jawbone and raised his bow.

Mr. Beltramini firmed his posture, arms held loosely at his side.

“There’s a train wreck about to happen,” Carletto said.

“I see it coming,” Pino said.

Pino’s father played the opening strains of the melody of “Nessun Dorma,” or “None Shall Sleep,” a soaring aria for tenor in the third act of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Turandot. Because it was one of his father’s favorite pieces, Pino had listened to a recording performed by Toscanini and the full La Scala orchestra behind the powerful tenor Miguel Fleta, who sang the aria the night the opera debuted in the 1920s.

Fleta played Prince Calaf, a wealthy royal traveling anonymously in China, who falls in love with the beautiful but cold and bitchy Princess Turandot. The king has decreed that anyone who wishes to have the princess’s hand must first solve three riddles. Get one wrong, and the suitor dies a terrible death.

By the end of act 2, Calaf has answered all the riddles, but the princess still refuses to marry him. Calaf says that if she can figure out his real name before dawn he will leave, but if she can’t, she must willingly marry him.

The princess takes the game to a higher level, tells Calaf that if she finds his name before dawn, she’ll have his head. He agrees to the deal, and the princess decrees, “Nessun dorma, none shall sleep, until the suitor’s name is found.”

In the opera, Calaf’s aria comes with dawn approaching and the princess down on her luck. “Nessun Dorma” is a towering piece that builds and builds, demanding that the singer grow stronger, reveling in his love for the princess and surer of victory with every moment that ticks toward dawn.

Pino had thought it would take a full orchestra and a famous tenor like Fleta to create the aria’s emotional triumph. But his father and Mr. Beltramini’s version, stripped down to its tremulous melody and verse, was more powerful than he could have ever imagined.

When Michele played that night, a thick, honeyed voice called from his violin. And Mr. Beltramini had never been better. The rising notes and phrases all sounded to Pino like two improbable angels singing, one high through his father’s fingers, and one low in Mr. Beltramini’s throat, both more heavenly inspiration than skill.

“How are they doing this?” Carletto asked in wonder.

Pino had no idea of the source of his father’s virtuoso performance, but then he noticed that Mr. Beltramini was singing not to the crowd but to someone in the crowd, and he understood the source of the fruitman’s beautiful tone and loving key.

“Look at your papa,” Pino said.

Carletto strained up on his toes and saw that his father was singing the aria not to the crowd but to his dying wife, as if there were no one else but them in the world.

When the two men finished, the crowd on the hillside stood and clapped and whistled. Pino had tears in his eyes, too, because for the first time, he’d seen his father as heroic. Carletto had tears in his eyes for other, deeper reasons.

“You were fantastic,” Pino said to Michele later in the dark. “And ‘Nessun Dorma’ was the perfect choice.”

“For such a magnificent place, it was the only one we could think of,” his father said, seeming in awe of what he’d done. “And then we were swept up, just like the La Scala performers say, playing con smania, with passion.”

“I heard it, papa. We all did.”

Michele nodded, and sighed happily. “Now, get some sleep.”

Pino had kicked out a place for his hips and heels, and then taken off his shirt for a pillow and wrapped himself in the sheet he’d brought from home. Now he snuggled down, smelling the sweet grass, already drowsy.

He closed his eyes thinking about his father’s performance, and Mrs. Beltramini’s mysterious illness, and the way her joking husband had sung. He drifted off to sleep, wondering if he’d witnessed a miracle.

Several hours later, deep in his dreams, Pino was chasing Anna down the street when he heard distant thunder. He stopped, and she kept on, disappearing into the crowd. He wasn’t upset, but he wondered when the rain would fall, and what it would taste like on his tongue.

Carletto shook him awake. The moon was high overhead, casting a gunmetal-blue light on the hillside, and everyone on their feet looking to the west. Allied bombers were attacking Milan in waves, but there were no sightings of the planes or of the city from that distance, only flares and flashes on the horizon and the distant rumor of war.

. . .

A conversation with Mark Sullivan

Q: A self-described adventure nut, you’ve said you’re attracted to stories where characters are pushed to their limits and Pino Lella, the hero of Beneath a Scarlet Sky, is definitely one of these characters. He risked his life guiding Jews across the Alps into neutral Switzerland, then became a spy inside the German High Command. The unlikeliest of heroes, he witnessed unspeakable atrocities that pushed him to his limits. What made him able to do this? What set him apart from so many other people at that time?

A: I am interested in heroes who are pushed to their limits, forced to go beyond themselves, and Pino is certainly one of them.

After spending eleven years with this story, I came to believe that Pino was able to survive all these incredible situations because of his basic decency, his gratitude, and his love of life; because of his deep emotional intelligence; and due to his fundamental belief in the miracle of every moment, even the darkest ones, and in the promise of a better tomorrow, even when that promise was not warranted.

That philosophy, or internal compass, if you will, enabled Pino to go beyond who he was, to turn selfless in moments of crisis. He conquered the dangers in the winter Alps by focusing on the people he was saving, their emotions and longings. As a spy I think he believed overwhelmingly in the value of his mission, and he felt compelled to bear witness to the atrocities committed by Nazis in Italy.

Pino also extraordinarily young, and like any brash young man he rarely seemed to let doubt cloud his thinking, high in the Alps, or down in Milan in the presence of General Leyers. And, of course, Anna gave him strength.

Q: When you first talked to Pino in real life, he was reluctant to tell his story, believing he was more a coward than a hero. Yet, you convinced him to talk and ended up going to hear the story in Italy. Tell us about that.

A: The first time I called him from the states, he said he didn’t understand why I’d be interested in him. I told him that from what I knew of his story he was an uncommon hero. His voice changed and he told me he was more a coward than a hero. That only intrigued me more, and after several more calls he agreed to my coming to Italy to hear the story in person and in full.

When I first went to see him I stayed for three weeks. He was seventy-nine, and living in a decaying old villa in the beautiful town of Lesa on Lake Maggiore north of Milan. I lived in an apartment on the third floor of the villa with a view of red tile roofs, the water, and the Alps beyond.

Pino was raised fluent in Italian, French, and English. He’d also lived in California for more than thirty years, so there was no need for an interpreter.

We talked for hours in his drawing room which was filled with old tapestries, and paintings, a grand piano, and the mementos of a long, fascinating life. Hours, days and then weeks went by as I listened to him summon up the past.

But by the time I got to Pino, more than six decades had passed. Memories change and fade with time. And a tortured conscious mind will block out traumatic events, bury them in the subconscious, or shade them so the victim can look at them from a tremendous distance, and with little emotion.

He was evasive at times. He had a self-deprecating nature and often downplayed his role and the dangers he faced. I often had to press him to just describe what happened versus filtering it through his meanings. Then the deeper story began to surface.

We laughed. We cried. We became friends.

It ended up being one of the most emotional and rewarding experiences of my life.

Q: Throughout the war, while others watched and feared, Pino risked and acted without regard for his own life. Yet as selfless as he was, in the moment that mattered most, he put life before love. Tell us about that, and if he’s been able to move past it.

As I listened to the story, I, too, was struck at how intrepid and selfless he’d been.

In the Alps, at 17, Pino guided Jews from the Catholic boy’s school in the dead of winter over the Alps into Switzerland, sometimes putting people on his back and skiing them to safety. Later, when he became the driver to a powerful Nazi general, and so a spy, he risked his life again and again to get information to the partisan resistance and to the Allies.

Because he wore the German uniform, Pino was thought a traitor by many people who did not understand his role as a spy, including his own brother. He got through the isolation through his love affair with Anna, the maid of the mistress to the Nazi general Pino drove for.

Anna is six years his senior, a woman with a mysterious past, but she becomes Pino’s confidante and his lover. Anna is his refuge, one of the few places he can turn to for sanity and hope for a future beyond the war.

But, as you mentioned, there comes a moment late in the book, and in the war, when chaos and anarchy is reigning in Milan, and Pino is forced to choose between life and love.

That scene is the emotional crucible of the novel, and one I had to pry out of him more than 60 years later.

When he reluctantly and vaguely first described the scene to me, Pino showed distinct discomfort, and claimed he never saw the event personally, that he was told about it by the old concierge with the thick glasses, and that it took place somewhere in the streets of central Milan. He was rattled even by that admission, wept briefly, and then stared off for a long time.

He asked if we could talk about other things. We did, but as that afternoon wore on into night, normally-cheerful Pino became dark and agitated. He asked to rest until morning.

Late that evening, from my apartment upstairs I heard him playing piano, a stormy and thunderous piece that I did not recognize. The next morning, he looked exhausted and said he had not slept well. The morning after that he looked ruined, and told me he’d suffered repeated nightmares of the event as an eyewitness.

His descriptions of the nightmare version were incredibly detailed, and recounting it crushed him physically and mentally.

He sobbed to me, “I said nothing. I did nothing.”

Pino’s anguish was so raw and palpable, it rocked me to my core. I did the only thing I could, and went to hold the old man while he poured out his grief and torment.

In the novel, the reader gets the dream version of Pino’s terrible dilemma because I believe the dream version is closer to the truth of what actually occurred to him during the sinister last days of the war in Italy, and I wanted the reader to travel the same gut-wrenching road.

Did Pino move past that moment and the war?

If you were to gauge that by the way he acted on a day-to-day basis during our reliving of his life at seventeen and eighteen, and in the subsequent decade I spent research, I’d say yes, absolutely. Pino was and is one of the most cheerful, considerate, and giving people I’ve ever met.

But the morning he described the nightmare to me was an entirely different story. He looked like he’d seen a ghost and been cast in a bitter trance. I will never forget his expression as long as I live.

Q: You have a background as an investigative journalist for both newspaper and magazines, why didn’t you tell this story as straight narrative non-fiction?

A: That was the original intent, but after years of trying to dig up the documented, fully-corroborated story, I threw up my hands.

So many other characters had died before I heard about Pino Lella, and the Nazis had burned so many documents surrounding his story that even after ten years of research I had to make informed assumptions in the narrative.

Once I surrendered to that, I knew I was in the realm of historical fiction and writing a novel. I gave in to it and adjusted by switching obligations.

The obligations of the non-fiction writer and the novelists are different. The former must hew to the documented facts and eye-witness accounts. The latter should dig for a deeper, emotional truth.

I went in that direction, and am glad I did.

Q: The book is dedicated, in part, to “Robert Dehlendorf, who heard the tale first, and rescued me.” On the way to the dinner party where you learned about Pino Lella, you contemplated suicide and “prayed for a story, something greater than myself, a project I could get lost in.” You were saved by that story. What saved Pino? Tell us about your friendship and what Pino has meant to you.

A: January of 2006 was a terrible time for me. My brother had drunk himself to death the prior June. My mother had drunk herself into brain damage. I’d written a book no one liked and was involved in a lingering business dispute.

That day I realized darkly that my insurance policies were more valuable than my life and potential in the future. During a snow storm, I seriously considered driving into a bridge abutment on an interstate freeway near my home, but I was saved by thoughts of my wife and sons. I was as shaken as I’ve ever been, and did indeed pray for a story.

Believe it or not, that very night at a dinner party I was forced to attend by my sick wife in Bozeman, Montana of all places, I heard the first snippets of Pino Lella’s tale. Larry Minkoff, a fellow writer, told me he’d heard a little about Pino, and his story, but wasn’t going to pursue it.

Minkoff introduced me to Bob Dehlendorf. Dehlendorf had been successful on Wall Street before moving out west and buying the ranch where Robert Redford shot the “Horse Whisperer”. He also owned a small ski area in California and was fascinated by World War II.

In the late 1990s, Dehlendorf was on an extended vacation in Italy when he met Pino by chance. Dehlendorf was a few years younger, but they bonded. After several days, Dehlendorf asked Pino about his experiences during the war.

Pino had never told anyone, but felt like it was time, and started telling him about Father Re and the escapes, and the Nazi general he’d driven for.

Dehlendorf was stunned. How had the story never been told?

That was my reaction as well, and that was enough to get me on a plane to Italy.

Over the course of those first three weeks, as Pino opened up more and more, I experienced his deep pain and marveled at his ability to go on after being so depressed and traumatized he too had contemplated suicide. I had to comfort him repeatedly during the course of his long recounting, and I was moved again and again.

During that time, and apart from the details of his war story, Pino taught me about life and his values and the many, many joys he’d been blessed with after handing over General Leyers to U.S. Paratroopers on the last day of the war. It made me realize how much I’d put in jeopardy even thinking about suicide.

I had a great, loving wife, and two remarkable sons. I had an amazing story to tell. I had a new and dear friend. I was more than lucky. Leaving Italy that first time, I felt blessed to be alive.

I went home a different person, grateful for every moment, no matter how flawed, and determined to honor and tell Pino’s story to as many people as possible.

I just never thought it would take that long.

Q: You spent almost nine years researching this story, hampered, in part, by a kind of collective amnesia concerning Italy and Italians during WWII, and the widespread burning of Nazi documents as the war ground to a close. The Nazi occupation of Italy and the underground railroad formed to save the Italian Jews have received little attention. Why have historians taken to calling Italy “The Forgotten Front”?

A: It did take me an awful a long time to dig up the details that surrounded Pino’s story. Remember I was trying to write this as non-fiction, and I wanted to nail the factual narrative.

Over the years and between projects, I spent weeks in the Nazi War Archives in Berlin and Friedrichsburg, Germany and in the U.S. Archives in Maryland. I went back to Italy twice more, and to Germany a second and third time. All along the way, I was hampered by the burning of Nazi documents in the last days of the war, especially by Organization Todt.

The OT, as it was known, was like a combination of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Quartermasters Corps. The OT built fortifications across Italy and Europe. The OT manufactured or stole everything the German military needed, from cannons to uniforms, from ammunition to food. It did so on every front of the European theater by using slaves. Millions of them.

Every time Hitler invaded a new country, he took every able-bodied male and called them “forced workers”. These slaves fortified the Russian Front. They built the western wall of pill boxes, tank traps, and artillery emplacements that U.S. soldiers faced on D-Day. They built the Green and Gothic battle lines in Italy. They even built the concentration camps.

The Germans were fanatical record keepers, but by the time Italy was freed there was very little left describing the OT and the million plus slaves believed to have toiled for the Nazis during the occupation. This was true everywhere I looked. It is estimated that as many as eleven million people were forced to work for the OT across Europe, and yet the documents still in existence about a vital part of Hitler’s war machine would fill less than three filing cabinets.

As you mentioned, there was and is a collective amnesia concerning Italy and Italians in WWII. It’s due in part to the savagery that so many Italians like Pino Lella witnessed in the last days of the conflict. Northern Italy descended into anarchy, and public revenge killings were widespread. It was so bad that many brave partisan fighters shut their mouths and never spoke of what they saw as the Nazis fled toward the Austrian border.

One old partisan told me they were young and wanted to forget those terrible times. “No one talks about the war in Italy,” he said. “So no one remembers.”

I also think historians have tended to ignore Italy because General Eisenhower decided to pull multiple divisions out of Italy in the late spring of 1944 to bolster the fight for France. After liberating Rome in June of that year, the progress of the weakened Allied forces remaining in Italy ground to a virtual halt. And the focus of journalists, historians, and novelists turned largely to the drama of D Day and its aftermath.

I think that worked in my favor to a certain extent. WWII Italy felt overlooked and unexamined, which made it even more exciting for me as I worked on the book. I realized very early on, for example, that in addition to Pino’s story I could tell the broader history of the fight for what Winston Churchill called “the soft underbelly of Europe.”

Q: Despite some tolerated revenge killings in the immediate aftermath of the war, Italian authorities conducted relatively few trials of collaborators. General Leyers, who by his own admission sat at the left hand of the Fuhrer, and who was arguably the second-most powerful man in Italy during the last two years of World War II, was among those never prosecuted. Explain the “Missing Italian Nuremberg,” and how General Leyers literally got away with murder.

A: That story is another reason war-time Italy has not received its due attention.

For almost two years after the end of the conflict, Allied prosecutors prepared cases against prominent Fascists and Nazis accused of war crimes in Italy. One of those Germans held awaiting trial was the man Pino drove for: Major General Hans Leyers, who ran the OT in Italy and answered directly to Adolf Hitler.

It’s hard to underestimate Leyers’ power. His formal title was Generalbevollmächtigter fur Reichsminister für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion für Italien. It translates as ‘Plenipotentiary to the Reich Minister for Armaments and War Production in Italy.’

By his title, he was a “plenipotentiary’, which meant he acted with full authority of Reichsminister Albert Speer. In reality he acted with the full authority of Hitler.

What Hitler and his generals wanted, Leyers built, manufactured, or stole. Like the master builders of Egypt’s Pharaohs, he did it with slaves. Pino drove for Leyers, and witnessed the vast armies of forced workers under the general’s total command. He saw men worked to death and brutally treated by Leyers’ men.

But the general was never tried, and was released from a POW camp outside Innsbruck, Austria twenty-three months after the war’s end. For years, I had no idea why.

Then, in interviews I conducted in Germany in 2016, Leyers’ daughter, his former religious minister, and his former aide told me that the general was released after testifying in secret against Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect, the head of the entire OT, and the only member of the Fuhrer’s inner circle to escape the hangman’s noose at the war crimes trials at Nuremberg.

Speer was ultimately sentenced to twenty years in Spandau Prison for taking slaves. The minister and Leyers’ aide also claimed that Leyers had presented prosecutors with evidence that he’d helped Jews and Catholics who’d been in mortal danger in Italy under Nazi occupation. The truth is a little more complicated.

By the spring of 1947, the world was growing weary of the war crimes trials, and wanted to move on. Communism had gained a foothold in Italy, and the Allies began to fear that conducting open trials against Nazis and Fascists might turn the country more toward Russian influence. With little fanfare, the plans for an Italian Nuremberg were dropped. The trials never happened.

The crimes and the charges were buried. Leyers and other men responsible for atrocities were set free, and subsequent generations of Italians were left with little shared memories of what exactly had happened in northern Italy during the war.

Q: Why didn’t Pino Lella talk about his experiences for more than sixty years? Is that unusual?

A: It’s not unusual. As I researched the book I found that heroes and tragic victims of the Italian battlefront were commonplace, and often intentionally unheralded or un-mourned.

Pino and many, many others who survived the war in Italy blocked out their experiences. They, like Pino, witnessed men and women at their most noble and at their most savage. They, like Pino rose to challenge after challenge, responded, and in victory and in tragedy promptly buried their memories, and told no one.

In my experience older Italians don’t talk freely about the war. To younger generations it’s as if it never happened. One old partisan fighter I interviewed told me that when he reluctantly went to a high school in Milan recently at the request of a history teacher to talk about the war, the students laughed at him. They said the things he’d seen could never have happened.

And it wasn’t just Italians.

As I relate late in the book, the father of one of my close childhood friends was in the U.S. Army and fought in Italy. Peter never talked about the war, and would deflect questions about his service. After he died, my friend was rummaging through his dad’s attic and found a box that contained a silver star for valor and a citation for Peter’s acts of selfless bravery at Monte Casino, one of the most brutal battles of World War II, on any front. Like Pino, he’d told no one.

Q: In real life and in the book, Pino was surrounded by brave, talented people who accomplished great things during, and after, the war. Tells us about Pino’s family and friends who became national heroes, “Righteous Among Nations,” fashion designers, racecar drivers, and even a saint.

A: Not quite a saint. Ildefonso Schuster, the Cardinal of Milan during and after the war, worked to save the city and the Jews under Nazi occupation. He knew about and encouraged the Catholic underground railroad that formed to get Jews out of Italy, many of them over the Alps in the winter of 1943-44. After Cardinal Schuster’s death, the future Pope John Paul II took up Schuster’s cause for sainthood and beatified him. Schuster’s blessed body lies in a crystal case beneath the Duomo cathedral in central Milan.

Father Luigi Re ran Casa Alpina, the Catholic boys school high in Italy’s northern mountains where Jews and other refugees gathered before making the brutal climb to Switzerland. Father Re organized the escapes. Pino, his brother, Mimo, and other boys were the guides. For selflessly risking his own life again and again, Father Re was recognized by Yad Vashem, the Israeli World Holocaust remembrance center as among the ‘Righteous Among Nations.” He is buried on the side of the mountain above the old school site.

Father Giovanni Barbareschi, a confidante of Cardinal Schuster, and the forger for the underground railroad was also recognized as among the Righteous Among Nations for his role in helping Jews escape Italy. Barbareschi, Re, and other priests and nuns, and ordinary Catholics risked their own lives repeatedly to save others, which helps explain why 41,000 of the estimated 49,000 Jews living in Italy before the invasion managed to survive.

Pino’s parents and extended family were in the fashion business in Milan. His mother and father designed and manufactured high-end purses. His aunt and uncle designed and manufactured fine leather goods sold all over the world. The Lellas and the Albanese family were also part of the resistance movement that sprang up soon after the Nazis invaded and set up Depose Fascist Dictator Benito Mussolini in a puppet government in September of 1943. The Lellas were active in promoting Milan as a global center of fashion until the day they died.

Pino’s younger brother, Mimo, was cited for heroism after the war for standing down a company of Nazi soldiers and placing them under arrest at the age of sixteen. He went on to found Lella Sport, a company which manufactured ski- and athletic-wear.

Pino’s cousin, Licia Albanese, fled to America before the invasion, and spent the rest of her long career as a soprano singing leads at the New York Metropolitan Opera under the direction of Arturo Toscanini. She died in 2014.

Alberta Ascari, who taught Pino to drive, lived his childhood dreams and became an Italian national hero. Driving for Ferrari, Ascari was World Grand Prix Champion twice. He died during a practice run on the Monza track in 1954. Fifty thousand people showed up for his funeral at the Duomo. He is considered one of the greatest race car drivers of all time.

U.S. Army Major Frank Knebel returned to California and became a newspaper publisher. When he died he left behind cryptic notes about wanting to write an account of “great intrigue” that unfolded in Milan in the last days of the war. He never did.

Carletto Beltramini, became a salesman for Alfa Romeo, lived all over Europe, and was a close friend of Pino Lella’s until the day he died.

Major General Hans Leyers moved to the small German town of Eischweiller upon being released from POW camp after the war crimes charges were dropped. Leyers had a great deal of wealth, but its source remains unclear. He and his wife had the money to restore a manor house on a large estate she inherited. He built a church and ran the estate until his death in 1983. As Leyers had predicted to Pino during the war, he had done well for himself before Hitler, during Hitler, and after Hitler.

Pino Lella is 91, and still lives on Lake Maggiore where he can see north to the Alps.

Q: You’ve said that global bestselling author James Patterson, your co-author on the Private series, “gave you a master class in commercial fiction.” What are some of the lessons he taught you, and how have they changed your writing life?

A: Mr. Patterson did give me a master class in commercial fiction. I’d written ten novels before he asked me to collaborate with him, and I thought I knew what I was doing.

I didn’t. Not really.

For the most part I’d winged it in my earlier works of fiction, writing draft after draft before the real story appeared. Patterson believed in thinking out the plot up front.

I struggled a bit, but soon came around to his way of thinking, which was essentially that novel writing was like house building. You have to be an architect first, and design the layout and frame before you start thinking about anything else.

Patterson also taught me that we were entertainers not educators, and that our stories were driven by suspense and mystery, but focused on emotion. He really hammered that into me, and I think my writing’s improved vastly because of it.

Beneath a Scarlet Sky is an epic tale told on a sprawling canvas, but I tried to stay aware of the pace of the story at all times. I did it by remaining focused on the emotions that radiated off Pino when he first told me his story.

- Beneath a Scarlet Sky is a work of historical fiction. As you were reading did you feel that the story was authentic? Given that the truth about what actually happened to each character is included at the end, talk about how Mark Sullivan crafted an interesting story while also sticking to the facts.

- Throughout the book, Sullivan describes horrific scenes filled with violence, bombings and ruthless executions. How well do you think he captures the fear in the air? Does he strike the right balance between page-turner and paying homage to the brutal truth?

- At the beginning of Beneath a Scarlet Sky, bombs are dropped on Milan, destroying sections of the city. At this point, Mr. Beltramini’s grocery is saved. In talking to Pino Lella, Beltramini says, “If a bomb’s coming at you, it’s coming at you. You can’t just go around worrying about it. Just go on doing what you love, and go on enjoying your life.” What are your thoughts about his advice? Given what’s going on in the world today, do you live in fear of terrorism or war? How do you balance “enjoying your life” in spite of your fear?

- If you or members of your book discussion group lived through World War II, here or abroad, how do your recollections match the emotions that you are reading here?

- Father Re enlists Pino’s help to usher Italian Jews through the mountains to Switzerland and to safety. Catholics and Jews clearly have different belief systems. In today’s world, what do you think it would take for a Christian to help, say, a Muslim in a similar manner in a place of war? Do you think it’s possible for such an underground network to exist today?

- Mrs. Napolitano is a pregnant Italian Jew who successfully escapes over the mountain pass in the dead of winter, in one of the most dramatic passages in the book. She almost dies along the way. If you were in her shoes, do you think you’d be brave enough to attempt the trek? What does it mean to be brave in the face of death?

- There is a moment when Colonel Rauff, the head of the Gestapo in Milan, helps Father Re’s boys corral oxen into a pen. He enjoys himself and almost seems…human. What do you think the author intended by choosing to portray such an evil man in this light? Was it effective?

- Just a few months shy of Pino’s 18th birthday, his father calls him back to Milan and demands that he enlist instead of waiting to be drafted. The catch? Enlisting with the Germans is safer. He is given a choice and chooses to enlist. Knowing you’d have to work for the enemy, what would you have done if you were in Pino’s shoes?

- Almost by chance, Pino becomes the driver for one of the highest-ranking German officers in Italy. It’s a chance for Pino to become a spy, once again risking his life. If you were Pino, would you take advantage of the opportunity, knowing it could put your family in significant danger?

- Pino’s best friend from childhood finds out that he’s a Nazi and accuses him of being a traitor. Pino can’t, of course, tell him the truth because it would put the mission in danger. What would it take for you to make a similar sacrifice? Is there a cause for a “greater good” that you’d risk anything for?

- Anna catches Pino in the act of rifling through the Major General Hans Leyers’ things. When he tells her the truth, she softens and they kiss. What was your initial reaction during that scene? Did you trust Anna? Why or why not? How did your gut feeling change as the novel progressed? Do you think she deserved her fate?

- After Pino and Major General Leyers are nearly killed by a British fighter plane, Leyers opens up to Pino and shares a bit about his life. Did this scene change the way you thought about him? Are people 100% evil, or is it possible to find humanity or goodness in everyone?

- Major General Leyers gives Pino advice: “Doing favors… they help wondrously over the course of a lifetime. When you have done men favors, when you look out for others so they can prosper, they owe you. With each favor, you become stronger, more supported. It is a law of nature.” How does this statement inform Leyers’ character? Do you agree with this statement? Is doing and receiving favors about “owing,” or is it about something else?

- Major General Leyers saves four sick children from Platform 21…and from death. Why do you think he does this? Out of the goodness of his heart, or is it one of his favors?

- When the Germans surrender, the Italians turn on each other and many butcher each other to death, either for doing nothing or for being friendly with the Germans. Are their actions justified? Or is this violence just as condemnable?

- Toward the end, Pino is given the chance to execute Major General Leyers. He doesn’t take it. Why do you think that is? What would you have done?

- The ending is quite a shocker. Did you see it coming? Why or why not?

- In certain sections, particularly in conversations between characters, Sullivan writes in a modern style. What effect, if any, does this have on the story or your perception of events? Does he capture the mood of the 1940s?

- Sullivan provides information about what actually happened to the characters in the novel. After completing the book and finding out their destinies, did you feel each character got what they deserved?

- In the preface, author Mark Sullivan admits to being suicidal the night he came up with the idea for Beneath a Scarlet Sky. Did that information have any impact on how you perceived the book?